Bo-Kaap

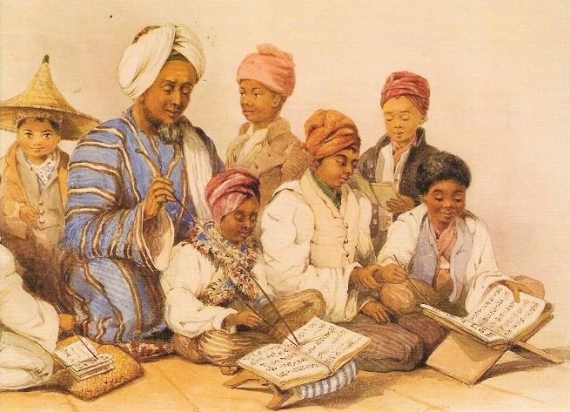

|

Bo-Kaap is one of the oldest urban residential areas in Cape Town. The earliest development of the Bo-Kaap area was undertaken in the 1760s. The house that today incorporates the Bo-Kaap museum building is one of the houses built that retains its original form and dates back to 1768. It was furnished as a house that depicts the lifestyle of a nineteenth-century Muslim family. Today, the museum is in a transformation stage. Although the Bo-Kaap has over centuries been home to people of various origins and religions, the area is closely associated with the Muslim community of the Cape. The first mosque at the Cape, the Awwal Mosque, was established through the endowment of a freed slave woman by the name of Saartjie van de Kaap and was built in the neighbourhood in 1804 and is still in use, although much altered over years. By the beginning of the twentieth century roughly half the population in the area was Muslim. Bo-Kaap's attractive, brightly coloured, flat-roofed houses, decorative mosques and the sound of the muezzin calling over the city streets have remained relatively undisturbed for all this time. The major threat facing this attractive area is now not forced removals, but gentrification, as image-conscious yuppies move into and renovate the lovely old buildings, taking advantage of the sea views and proximity to the city centre. The history of the Bo-Kaap reflects the political processes in South Africa under the Apartheid years. The area was declared an exclusive residential area for Cape Muslims under the Group Areas Act of 1950 and people of other religions and ethnicity were forced to leave. At the same time, the neighbourhood is atypical. It is one of the few neighbourhoods with a predominantly working class population that continued to exist near a city centre. In the mid-twentieth century, most working class people in South Africa were moved to the periphery of the cities under the Slum Clearance Act and neighbourhood improvement programmes. Over the years the Bo-Kaap has been known as the Malay Quarter, the Slamse Buurt or Schotcheskloof. The city of Cape Town is situated on the south western tip of the African continent, in one of the most beautiful natural locations in the world. The Cape Malay Quarter, or 'Bo-Kaap' which sprawls along the slopes of Signal Hill, bordering our city, presents a scenario of enduring historic and cultural significance. It's certainly worth taking the time to explore the area when you come to Cape Town. The establishment of the Cape Malay people evolved with the Islamic influences which became their religion and culture during the years of slavery in Cape Town in the 18th century and beyond. The Afrikaans language is thought to have developed as a lingua franca for the slaves, as well as their masters, to be able to communicate effectively. Educated Muslims were in fact the first to write texts in Afrikaans. Apart from the unique development of the Afrikaans language, the Islamic culture became embedded among the slaves when prominent Muslim noblemen, 'Orang Cayen' (men of power and influence) political exiles from Asia who had opposed colonisation of their countries by the Dutch, were 'banished' to the Cape. They were influentual in laying the foundations for Islam in the Cape slave community. The most prominent among the Orang Cayen was Sheikh Yusuf of Macassar (Indonesia), a revered Sufi scholar whose Karamat (shrine) is situated today at Macassar on the Cape Flats. The Muslim cemetery Tana Baru (meaning New Ground), where some of the earliest and most respected Muslim settlers of South Africa lie buried, was closed in terms of the Public Health Act No. 4 of 1883. Following the granting of religious freedom to Muslims in 1804, the Batavian government granted the first piece of land for a Muslim cemetery - Tana Baru - to Frans van Bengalen on October 02, 1805. Despite its closure the Tana Baru, situated in the Bo-Kaap, has always been regarded as the most hallowed of Muslim cemeteries in Cape Town. Three prominent early Cape Muslim Imams, namely Tuan Nuruman, Tuan Sayeed Alawse and Tuan Guru lie buried on the Tana Baru grounds and shrines have been erected to honour them. |